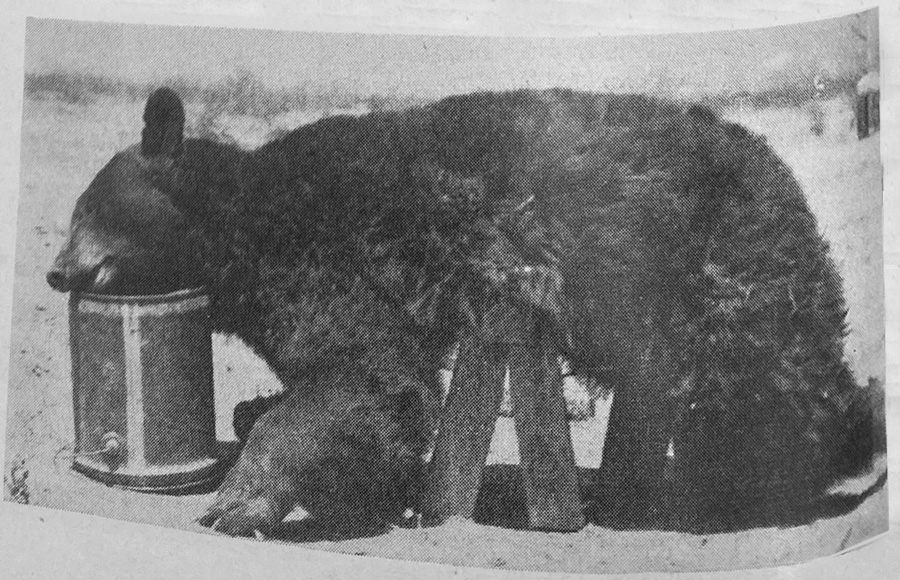

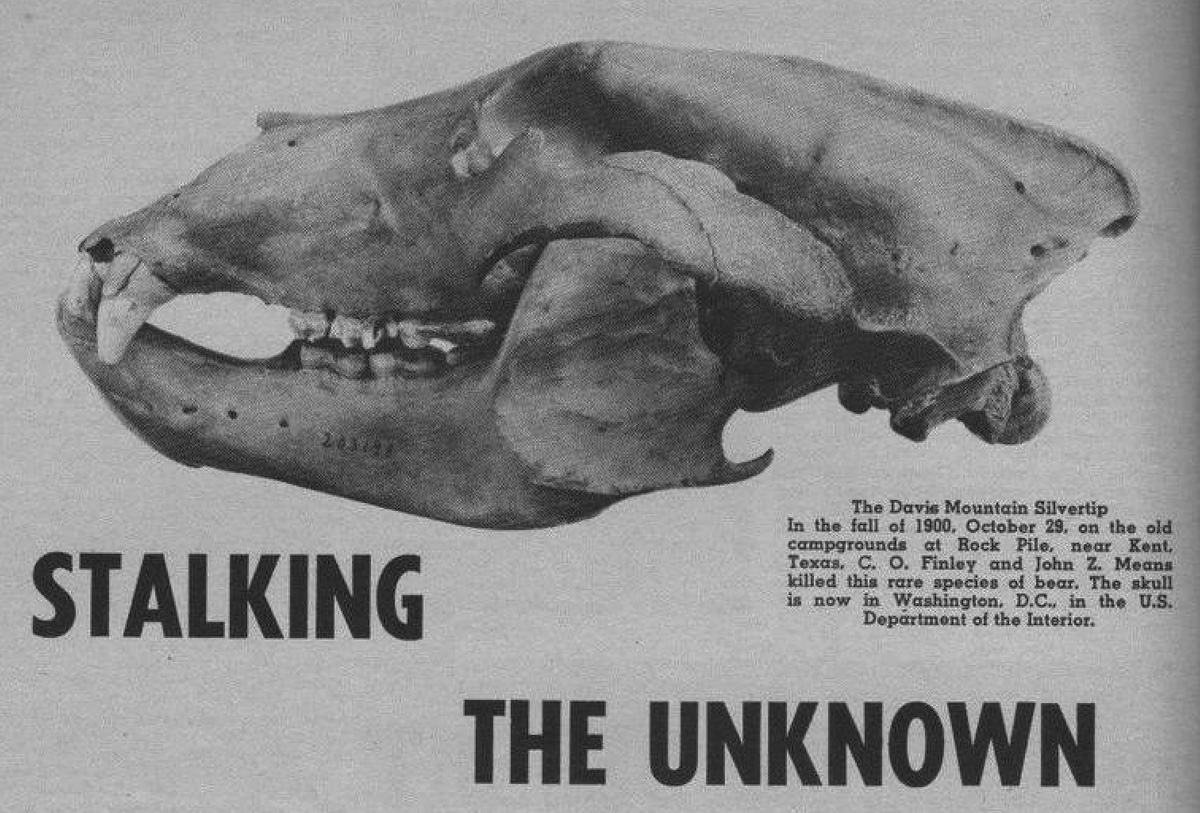

Above: A photo of the Texas grizzly skull from “Stalking the Unknown” by C.O. Finley, The Pecos News, July 2, 1965

Source: “A Texas Grizzly Hunt” by J.G. Burr, Texas Game and Fish Magazine, August 1948, p. 4 & “Stalking the Unknown” by C.O. Finley, The Pecos News, July 2, 1965

The grizzly bears’ historical range runs from Alaska through Texas and into Northern Mexico, but there is only one recorded instance of a grizzly actually being killed in Texas. This was during an annual bear hunt in the Davis Mountains in 1899. I had read about the bear, nicknamed “silvertip,” in Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine. The article is worth reading because it includes some interesting cultural contexts. The bear is also noted in Vernon Bailey’s “Biological Survey of Texas,” but the most interesting coverage can be found in the August 1948 issue of Texas Game and Fish Magazine.

There we find C.O. Finley, the hunter that killed the bear, relating the lengthy story of the hunt in his own words (with commentary from J.G. Burr). The article’s length makes it difficult to read in photographs, so I’ve transcribed it here in its entirety to make the primary source information within it more accessible. I have also included some images from “Stalking the Unknown,” the original article by C.O. Finley.

A Texas Grizzly Hunt

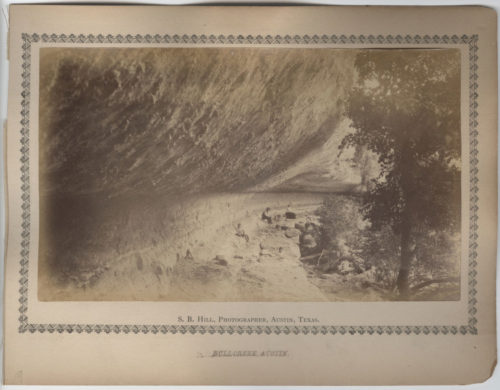

by J.G. Burr

Yes, there was once a grizzly bear hunt in Texas, and it has no parallel in the wild animal history of the State. It occurred in the Davis Mountains about fifteen miles southwest of what is now the site of the McDonald Observatory, and southeast of Livermore Peak at the head of Merrill Canyon.

In this setting C.O. Finley and John Means brought down the only grizzly bear ever known to have been killed in Texas. According to the record in the National Museum at Washington, the bear was killed on November 2, 1890*.

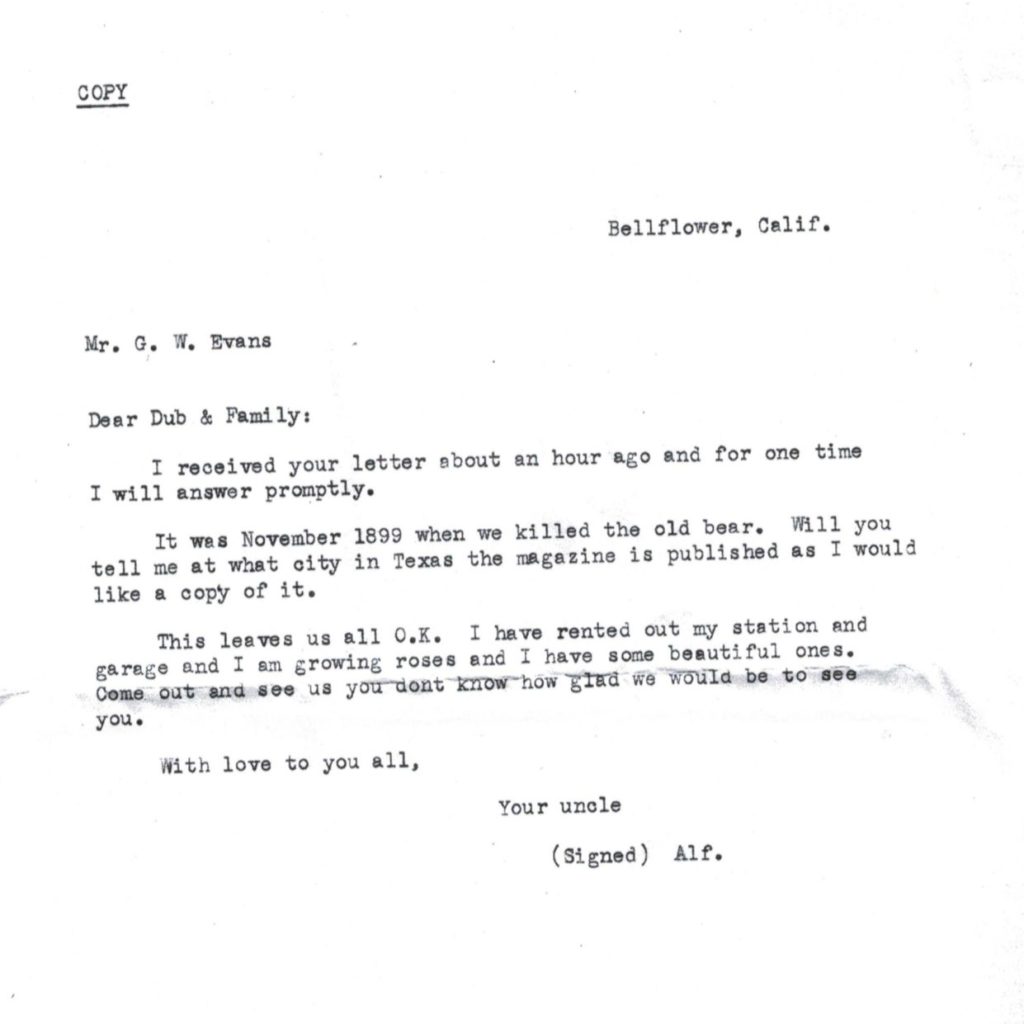

Eight years ago after the death of John Means. C.O. Finley sat down and made a written report of the hunt, and sent it to his brother, O.Z. Finley, the game warden now stationed at Lake Walk on Devil’s River. O.Z. Finley was doubtless in the hunting party and knew the story but the time had come to make a more complete record of the famous hunt that could be passed on to future generations. A brief note accompanied the write-up.

Dear Brother: “Am enclosing the history and kill of the bear hunt the day we killed the old grizzly bear. John and I had often talked of doing this but had put it off until now he is gone, and it is up to me, for I did not want to go (pass on) and leave the most eventful day ever spent in the Davis Mountains unwritten. So, file this away to read as often as you like and hand it down to your children and grandchildren.” This was written four years before C.O. Finley (Otie) died.

Very fortunate we are the public as well as the children and grandchildren are able to share the pleasure of this remarkable adventure. The name Finley reaches back to the pioneer days when Dr. and Mrs. D.T. Finely were among the earliest settlers in the Davis Mountains (1885). Will Evans, in his book “Border Skylines” refers to Grandma Finley as a person known and loved throughout the Tans-Pecos country. The Finley boys found good hunting in the H.O. Canyon where the family settled, and there they brought down the black bear and the antlered mule deer. Prominent in the new generation is Joe Finley, (son of O.Z.) manager and part owner of the Callaghan Ranch of South Texas where hunters bag some of the biggest bucks to be found anywhere in Texas.

It would be easy enough to abridge the story of the great bear hunt, but cold statistics should be warmed up a bit in order to get the feel of the players as they enacted that mountain drama of more than half a hundred years ago. Such an introductory warm-up is furnished by C.O. Finley as he proceeds to the story of how he and John Means killed the Davis Mountain silvertip, as the grizzly was called.

“I have been asked to write the true story of a bear hunt on which the only grizzly bear had ever been killed in Texas. As a prelude to this story, I will give a brief history of the beginning of what turned out to be an annual bear hunt by a member of the old pioneer ranchmen in the Davis Mountains.

“In early [eighteen] nineties, some seven or eight families of us, the Means, Evans, Marleys, Jones, Mayfields, Finleys and a number of others all met at what is known…. as the rock pile, near Saw Tooth Mountain, one of the most beautiful spots for camping in the Davis Mountains. Here we met several years prior to the noted year that we killed the old grizzly. In addition to our own families, we always had a number of friends from over a good part of Texas – from Ft. Worth, Dallas, San Antonio, and other parts to spend a week with us on our hunts. We also invited one or two ministers every year to our camp which was as clean and free of bad language as possible. Never an oath was heard nor a bottle of whiskey came to our camps.

Folks came from all over Texas to take part in The Annual Bear Hunt and Renew Acquaintances

“Our party usually ran from forty to seventy-five people; men, women, and children, and the dogs ran from young, untried hounds to old, tried and true bear dogs. We had from a hundred to one hundred and fifty saddle horses and always took three or four old-time chuck wagons and plenty of good Mexican cooks, as good ones as ever cooked a meal around a campfire, and they always kept plenty of warm grub to eat. We always had two horse wranglers by day and two by night (called night hawks) to guard or herd horses.

“In the morning the old cooks would be up early and have us a good hot breakfast ready before daylight (it was cool in the mountains) so we were always ready when our night hawks brought our horses up near camp by the time it was light enough for us to see how to rope our horses for the day’s ride. Such a time we had roping and saddling our horses! – All horses those days were not pets, and every morning before we could get saddled and out of camp, some would be pitching with their saddles and some with their riders, and very often some “old boy” would get pitched off and his horse would have to be caught. When every one was ready, which was never later than sun-up, and pretty cold in October and November in the mountains, some one would blow their horn and off we would go to the mountains, which was bear heaven.

“We hardly ever failed to get a bear and sometimes three or four during the day. And every day or so some one would get lost from the bear chase and kill a deer or two. While this was all good sport, especially if you go in the chase and got to the killing of the bear (which was sometimes up a tree or in a cave, or out in the open) it was awfully hard on the horses and men who rode hard and reckless in that rough country to follow and keep up with the hounds.

“When we got in to the camp of an evening, horses, men and dogs were usually all in; but a well-cooked meal, a little rest, and a few cups of coffee, and we were ready for a good talk and a prayer (of thankfulness) by one of the ministers.

“We would then clear us off a spot of ground and dance the old square dances for an hour or so, as we always had musicians and plenty of music in the camp. Then off to bed and a good night’s rest in our tents and on our old camp beds, and early the next morning we were ready for another day’s hunt. Some days we had fine luck and other days our luck was not so good.

“These hunts were made up of old men, young men, women and children old enough to ride. The women and children would stay as long as possible, but not often did they get in a chase after a bear and see him killed; they would drop out and a few of the older men would drop back to take care of them and see that they got back to camp. It was always uncertain which way a bear would run or how far. If he was fast he would probably not fun over a mile or two, but would climb a tree; but if he was poor he was always hard to stop and sometimes would get away entirely. When we found an old poor bear and failed to stop him, we always lost some of our dogs and they would not get in for sometimes a day or so, footsore and almost starved.”

That was the type of bear hunt that was of annual occurrence in those mountains and in those far away days. But there was one hunt that stood out above all others, and if you wish to go over the ground here is Mr. Finley’s picture of how it looked.

“Well, I started this story to tell you of the jolliest old days ever spent by our party or any other parties in the Davis Mts.., in the fall of 1890*.

“On the 29th of October we met at our old campground at the Rock Pile, about 75 of us, just as we had each year before, with everyone feeling good. The horses were fat and the dogs in good shape; we anticipated a good time, and we had it. We spent this first four days with just fairly good luck, getting a bear or two and some blacktail deer each day.

“On the second day of November, which was our fifth day hunt, we all left camp as usual about sun-up and went that morning right into the mountains. We traveled some eight or ten miles, crossing up near the head of what is known as Saw Mill Canyon just north of Livermore Peak, and on southeast over into the head of Limpia canyon. (Livermore Peak is next to the highest peak in Texas.) This is the canyon that port of Fort Davis is on, and in going from the head of Saw Mill Canyon through the mountain over into Limpia Canyon there is a gap this is called Bridge Spring Gap. Well, all of our party, at this time some thirty or forty people, went through the mountain over into Limpia Canyon, with the exception of John Means and myself As the party with all the dogs went on through the gap, we dropped back behind and turned south up the side of the mountain, topped out and rode along the top, parallel with the balance of our party and the dogs who were down in Limpia Canyon.

“All the country is very rough, full of canyons, bluffs and a lot of timber from shin-oak thickets to pines fifty feet high. Well, when John Means and I got out on top, we were possibly a mile or more from the balance of our party.

“We heard a dog yelp and then another and pretty soon the whole pack was running and yelping and the dogs and men rode up on a four year old fat cow that had been killed up on the side of the mountain and then dragged down the hill about 100 yards into a big thicket, and part of the cow had been eaten.

“It was then that the dogs had started trailing the old bear, and when the bear heard the dogs he pulled out from where he was bedded up near the cow he had killed, and ran out of the canyon south across the mountain, crossing out on top just ahead of John Means and myself; so we rode like drunk Indians to keep up in hearing of the dogs.

“Just after we had crossed their trail John looked around to the right and said ‘Otie, I see the old devil.’ He had gotten out on an open spot and stopped. Then we switched around some brush and rocks to where we could get a shot at him, but when we came out to where we could get that shot, the old bear was gone, and there sat four dogs, the only dogs out of the whole pack that would run the trail.”

There were various estimates to the number of hounds that started on the morning hunt, the highest being 52 but the more conservative (I will not say cowardly) members of the group began to drop out as the gravity of the chase began to appear. The hunters and even the dogs sense the danger of attacking an animal powerful enough to kill and drag a four year old cow a hundred yards. Clearly, a black bear or cougar could not have done such a thing. So the dogs, as the chase warmed up, were constantly backtracking. They would come trailing in and had to be urged to resume the chase. If you want the opinion of the writer, he is ready to assert that those hounds had a keen sense of the eternal fitness of things. If it is true that every dog has its day these dogs felt no urge to die on the field of honor. So, as they neared the finish, even the immortal four had to be urged to the fight; and continuing that account Mr. Finley said:

“Well, we mushed them a little and got them to go on. We got back on our horses and followed them about a mile and a half further over some very rough canyons and down into the head of Merrill Canyon. There the old bear had stopped again. Means and I had ridden as far as we could and had to leave our horses and walk down the mountain side to where we heard the dogs barking. When we got about a quarter of a mile from here they had stopped the bear, we me the four dogs all coming back, trailing along one behind the other to meet us. Well, we mushed them up again and got them to go back to where they had stopped the bear, which was down a deep, bushy, rough canyon. We located him standing with his head toward us in the brush, with the dogs standing off barking. We we got down to within about 125 yards of him, we sat down side by side on a small bluff of rocks with our little short saddle guns, 30-30, and began pumping lead into him.

“We evidently hit him with our first shots as he began to pitch and bellow like a wild bull, and made a dash at the dogs, but succeeded in catching only one old speckled bob-tailed hound that belonged to Bill Jones. The bear so tore up the dog’s jaws and neck that we had to kill the old fellow. He failed to catch the other dogs as they were younger and could get out of his way. Failing to catch the other dogs he came back and stopped in exactly the same place he was in when we made our first shots. We lost no time in shooting four more shots each into him and he just melted down on his old belly.

“We did not yet know what we had, but we knew he was an extra big bear. We took a little round and got about 100 feet above him and stopped to see if he was sure enough dead. We we were standing there, Means raised his gun and said, ‘Otie, hadn’t I better put one in his old head? He looks awfully big.’ And I said, ‘No, lets not tear his head up, as he looks awfully big and one of us might want to keep it.’ About that time a little black-and-tan hound that belonged to Joe Marley walked up and caught the bear by some hair and shook him a little. Then we knew the bear was dead and down we rushed to look him over. When we reached the bear we discovered the gray tips of his haid. John yelled like a Comanche and threw his hat as high in the air as he could and said, ‘Otie, we have got a grizzly!’ To say that we were excited is putting it very lightly. Well, we turned him over, opened him up and removed his insides, then turned him back again to drain. Then we went back up the mountain side out on top to where we had left our horses, and blew and blew our horns, and finally got eight more men to come to us. The party was scattered out over the mountains trying to locate the dogs and bear.

“We returned to the bear with the eight men but he was so large there was no way to take him back to the camp, so we took his hide off, leaving his feet and head on the hide and put the hide across the biggest, stoutest horse we had, and lit out for camp with the man who had been riding the horse, riding behind another man. We could not go straight through the mountains to camp and lead this horse with such a load, the weight of the bear being estimated at at least 800 ponds, and the head, and feet possibly four or five hundred pounds, so we had to go around and out of the mountains on the west side and out by my ranch. The horse that was carrying the hide had the thumps and almost had lockjaw so we had to turn him loose and get a pair of little Spanish mules and an old buckboard I had at the ranch to carry our hide on the the camp. This was about 20 miles from where we had killed the bear.

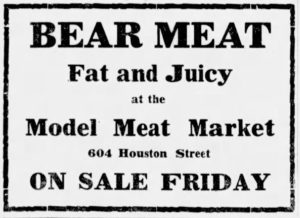

“It was about 9 o’clock that night when the ten of us with our three hounds got into camp with our kill, wornout and hungry, not having had anything to hear since before daylight that morning. You can imagine how good it looked to see those old cooks and their dutch overs filled with good warm camp grub, and that black coffee!

“When we had unsaddled and turned our tired and wornout poneys loose, and had unloaded and stretched the bear hide over a big rock, we were the most excited bunch of people ever seen. Everybody was talking, some asking questions and some telling their story of what happened. We all had seen a lot of this kind of thing for a good many years, but this was the biggest day’s hunting that had ever been pulled off in the Davis Mountains.

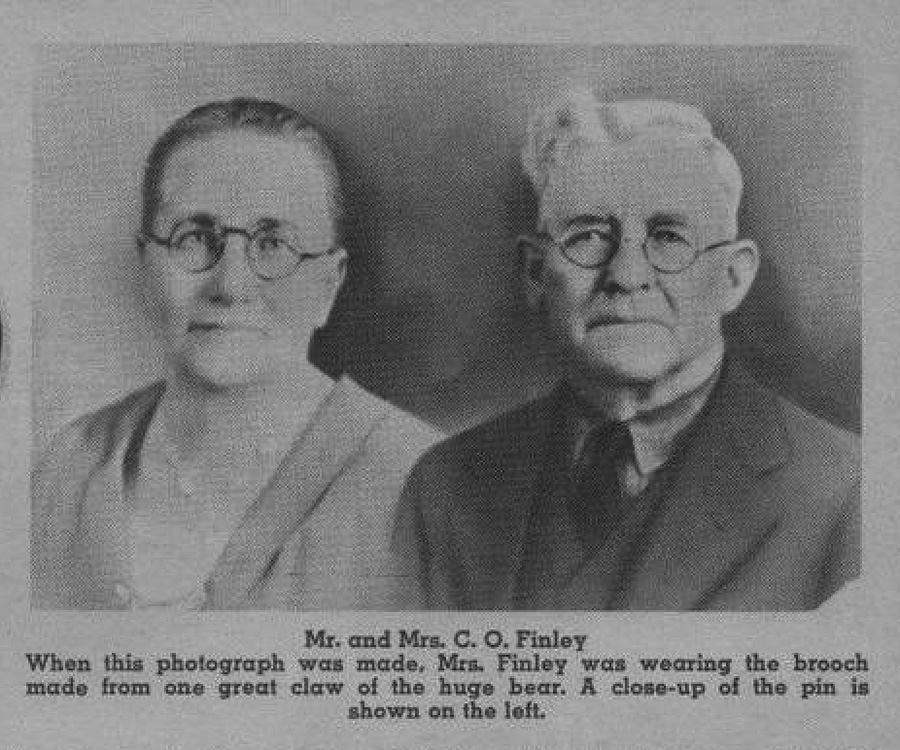

“The next morning we cut off his feet and found that he had only three claws on one of his front feet and one on the other. George Evans, John Means and I kept three of them and took them to El Paso and had them plainly mounted for watch fobs, and the fourth we gave to a good friend by the name of Tat Hulling who ranched at that time back north of Kent on the Delaware but who has since died. His widow lives in El Paso. Mr. Means and Mr. Evans always wore their bear claws for watch fobs, just as mounted, but they were so big and heavy I did not like to wear mine, so I had a pin put on it for Mrs. Finley to wear so that she wears a pin that is different from that of any other woman.

“The hide we sent to San Antonio and had it nicely dressed and gave it to Mr. L.S. Thorn who, at the time, was the general superintendent of the western district of the T. and P. Railroad and a good friend of ours as we shipped a good many cattle over his road in those days from Van Horn and Kent. Mr. and Mrs. C.O. Finley from “Stalking the Unknown” by C.O. Finley, The Pecos News, July 2, 1965″The hide we sent to San Antonio and had it nicely dressed and gave it to Mr. L.S. Thorn who, at the time, was the general superintendent of the western district of the T. and P. Railroad and a good friend of ours as we shipped a good many cattle over his road in those days from Van Horn and Kent.

“The head which I kept Mr. Means from shooting into I took home and boiled all the meat off in a big wash pot. I scraped it and cleaned it up well and hung it up over our front door outside, and never expected anything to be done with it other that to be seen and admired by all guests. However, that winter, a young man from the Biological Department at Washington came to the Davis Mountains to collect specimens of all kinds of ‘varmints’ and fowls that are to be found in the mountains. Asking for lodging at our ranch Mrs. Finley let him stay and during the winter he heard us talking about our past fall hunt and saw the bear’s head hanging out over the door. When he went back to Washington the next spring he related the story to the Department heads and they wrote and asked me to send it to them, which I did. After keeping it for several months, they sent it back with several long names attached to it that we couldn’t read, but pronounced it a real grizzly bear with the claim that there was no record of one ever having been found in Texas before.

“In about a year the Department wrote me again and asked me to return it to them, which I did, as they wanted to re-survey it. Then they wrote and asked me to buy it for the government, stating that it was a very rare specimen and that they would forever preserve it and attach any record to it that we might want to keep with it.”

Later, as the fame of this notable affair spread abroad an effort was made to have the bear head sent to the Dallas Fair as an exhibit. Unwillingness to loan the specimen for the use of the Fair is explained in a letter to Mr. Thomason which was transmitted to Mr. Finley as follows.

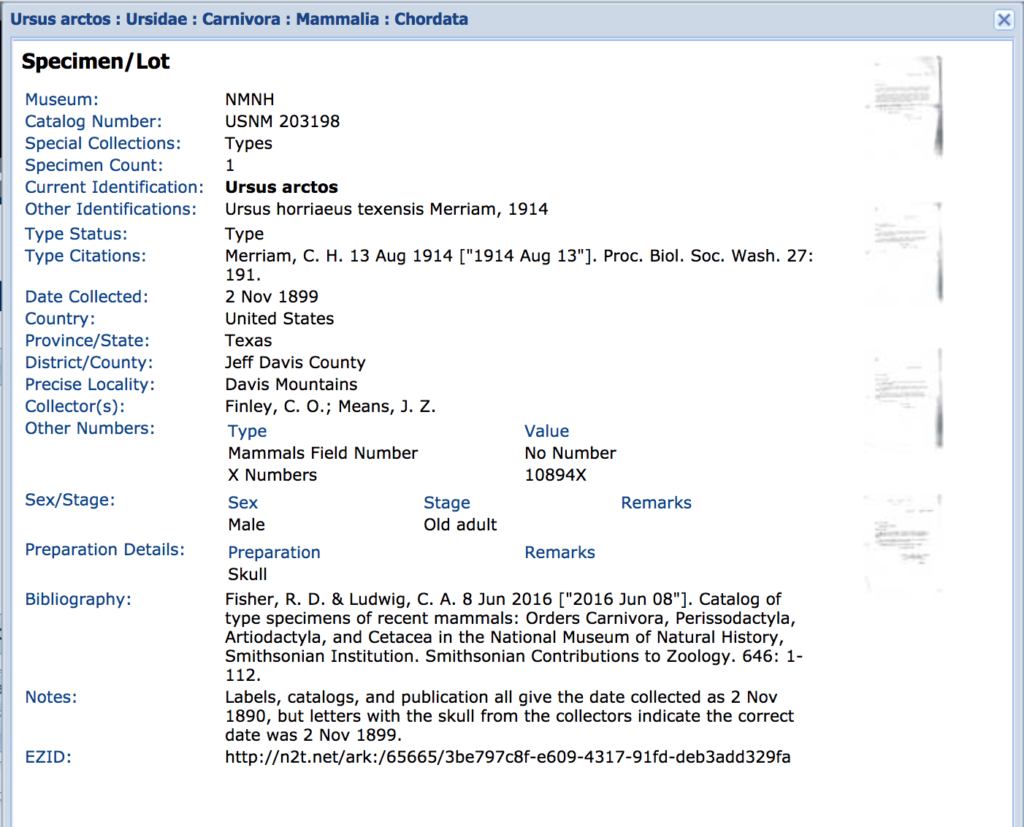

“‘Under any ordinary conditions we should be glad to arrange so that this specimen might be exhibited at the Fair. However, this particular speciment was used by Dr. C. Hart Merrian, former Chief of the Biological Survey, as the basis for a new race of grizzly bear, namely Ursus horriaeus texensis, and this particular skull is the type form selected for this race. In fact this skull is the only known specimen of its kind in the world.

“‘Because of the great value of these ‘types’ they are kept in fireproof, locked cases in the National Museum in order that they might be safeguarded against loss. I trust that Mr. Finley will appreciate the importance of safeguarding so valuable a specimen against loss or damage. It seems to us it would be exceedingly unfortunate to take a chance of subjecting this specimen to the risks of transportation and exhibitions at a fair. The teeth, especially, become very brittle and it would be impossible to avoid some damage, and if lost it could never be replaced. Even should another grizzly bear be taking in Texas, it would not be of the type form.

“‘While we appreciate the local interest there might be in the exhibition of this specimen at the Fair we would strongly recommend against doing so because of the importance of keeping it in perfect conditions for future generations. In this connection you be interested to know that the names of the men who collected the specimen are on the label and that credit was given in publication of the description of this ‘type” specimen. (Editor’s note:–See North American Fauna No. 25 by Vernon Bailey.)

“‘I hope this explanation of the situation will be satisfactory to Mr. Finley, and give him assurance that the greatest value the specimen will be conserved by leaving it undisturbed in its present location in the National Museum.'”

The letter was signed by W.B. Bell, Chief, Division of Wildlife Research.

The unique appearance of a grizzly bear in Texas opens a question of how it could have happened. The range of the grizzly extends from Alaska to well down into the mountains of western Mexico. The grizzly of northwestern Mexico is a sub-species called the Sonora grizzly, but Dr. Merriam in 1914 hitched on the sub-specific name texensis. Now, Taylor and Davis, in “Mammals of Texas,” published in 1947, have cut the name down simply to Texas Grizzly, Ursus texensis. A new Mexico grizzly corresponds to the Sonora, with the Texas species in between.

It seems likely that the Texas grizzly crossed over from New Mexico or Old Mexico and picked up characteristics that merited a new classification as a Texas mammal, or that such characteristics may have developed along the borderline of the two environments prior to the south or northward movement.

Bailey stated that the Davis Mountain specimen was an old male that in good condition could have weighed 1,000 pounds.

Charles Otis Finley died in 1944 at Pecos. John Zachariah Means died of pneumonia in El Paso in 1937. Mrs. Finley resides at Pecos.

*Wild Texas History Note:

The Texas grizzly skull still resides in the Smithsonian archives. If you visit their website at the link below, you can see the correspondence concerning the date when the bear was killed. George Evans corrects the record that the bear was killed in 1899 and not in 1890 as was stated in some sources. This makes sense in the context of some of C.O. Finley’s comments about how the annual bear hunt had been happening in the 1890s.

Comments are closed.